Q&A: Dynamics of Difference in Australia

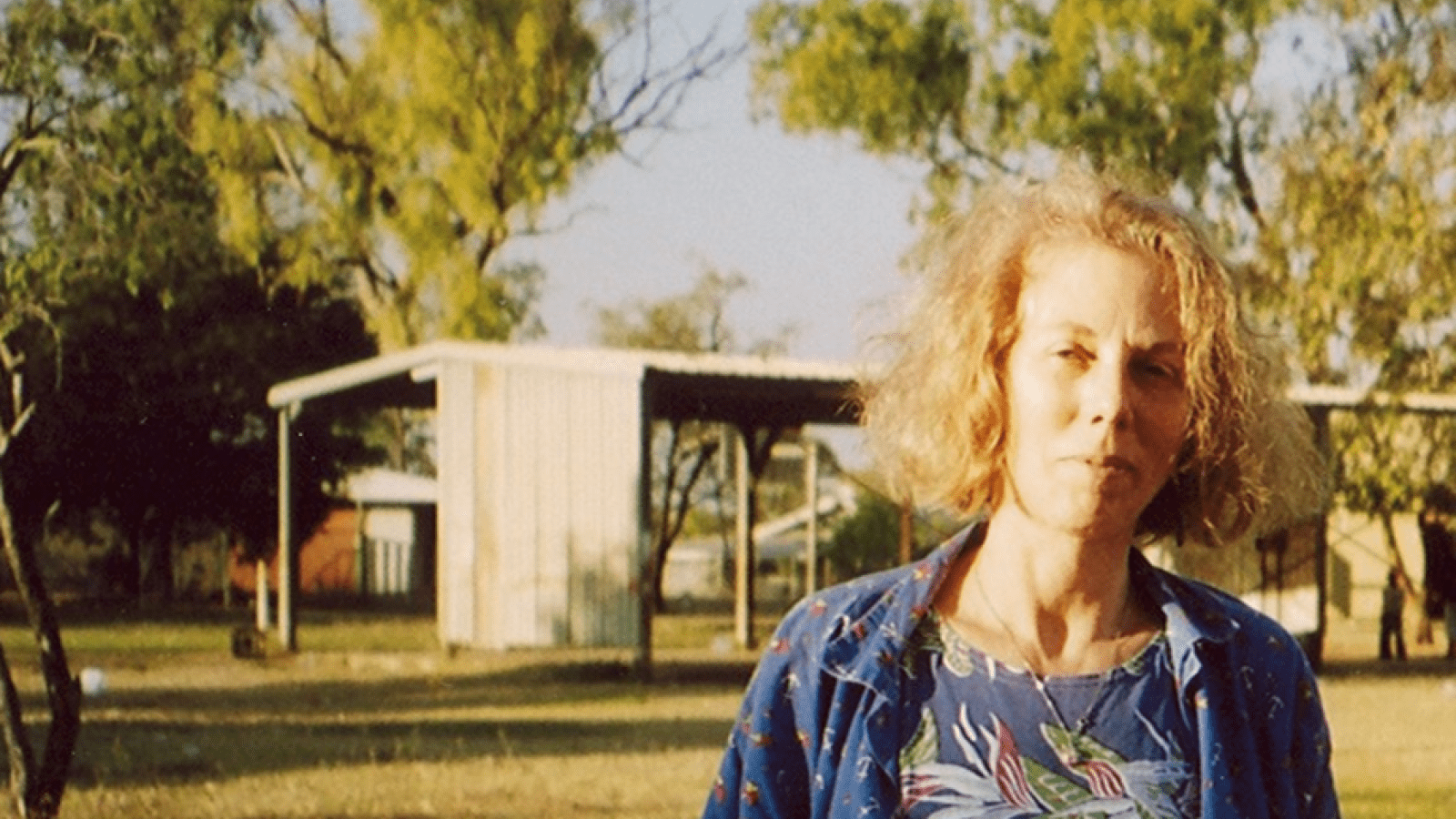

Professor Francesca Merlan. Image: supplied.

In her new book Dynamics of Difference in Australia: Indigenous Past and Present in a Settler Country, Professor Francesca Merlan explores relations between indigenous and nonindigenous people, from the time of first contact to present day.

Francesca Merlan is a Professor of Anthropology in the ANU School of Archaeology and Anthropology. Her areas of expertise include: social and cultural anthropology; studies of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander society; and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander languages. She has done research over many years in Northern Australia, as well as the Western Highlands of Papua New Guinea, and southern Germany.

You arrived in Australia in 1976 to do a research fellowship investigating the "changing locations and languages of indigenous people in an area of considerable social diversity". Can you talk about some of the research you went on to do in the proceeding decades, and the work you've done (e.g. land claims) with Indigenous communities?

I went to the town of Katherine in the upper Northern Territory shortly after my arrival in Australia in 1976. The town was ringed by indigenous fringe campers. Many of those people had previously lived on pastoral stations in or near their own traditional lands and were being expelled from them, mostly because of changes in award wages that had happened in 1968. Others had been in Katherine longer, after they or their parents been relocated to camps near there during World War II. Very few were of families which had been around the town area from well before that, having survived the earliest colonial period of murderous violence.

There was still little housing or any other provision for them in the town. Indigenous organizations were being established, and other town residents were beginning to learn that the indigenous people were not going away. They had come from all over the Top End of the Northern Territory. In 1976, there were something like fourteen different indigenous languages being spoken around town.

In their way of living, the differences that these indigenous people brought to town collided with the taken-for-granted norms of many non-indigenous townspeople – with regard to use of space, use of money, dress, fundamentals of social relations and comportment, and in other ways. That was the beginning of my sense of the differences, often incompatibilities, between indigenous and non-indigenous people that I explore in the book.

I have degrees in both anthropology and linguistics. Over the years I documented several of those previously unknown or little known indigenous languages extensively. Many are now moribund. Over that time, too, I became more deeply involved in various communities and camps around the town where indigenous people lived, and learned about the specificities of these communities and their relations with non-indigenous Australians.

My first research appointment was from 1976-9. This period was marked by conflict over indigenous-nonindigenous difference in the town and by the appearance of `rights for whites’ sentiment and groups. There was some progress in identification of living areas and service provision for indigenous people. The federal Northern Territory Aboriginal Land Rights Act come into effect in 1976 but for a couple more years, there was little land claim activity. Then there was a swell of land claims that has since seen about half the Territory made over to Aboriginal ownership.

By then I had lived in several indigenous communities and gotten to know a lot of people there. I became involved in several land claims, all over areas of Crown Land. These included the iconic Katherine Gorge National Park – now known as Nitmiluk - and Elsey Station – of We of the Never Never fame. That work involved documentation of the indigenous people’s relations to the land under claim. The knowledge required for these claims tended to come from adult, mostly senior, people. Meantime, entire communities were undergoing significant change – in location, in obvious deterioration of health for many, in changing relations to institutions and economic resources of the larger society. There were also changes in the terms of indigenous – nonindigenous relations, but differences and incompatibilities remain marked.

Can you briefly describe what your book covers? What are the sorts of differences between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians that you explore in your book?

Those differences obviously need to be understood historically as part of understanding the present. My book is unusual in attempting to identify dimensions of difference in the past and into the present, and theorizing the dimensions of continuity and discontinuity. Alongside my experience in the Territory, over the years I came to read a great deal of colonial history and related this to my own research experience.

I was very interested in the accounts of explorers, travellers, missionaries and others who interacted closely with indigenous people. Such accounts offered one of the best ground-level historical vantage points from which to understand indigenous reactions of many kinds to the unusual colonial arrival. This record revealed a diversity forms of encounter and outcomes – many of them very violent – and ways in which indigenous people were drawing upon their own social resources to fashion their relationships with outsiders.

Delving into the past record helped me think about how to theorize terms of encounter and difference that I was observing daily. It provided insight into Aboriginal people’s own ways of doing things and adapting to new circumstances – undoubtedly under conditions of inequality in both past and present.

Would you like to elaborate on one of these examples?

In many colonial histories – not only from Australia, but also Mexico, parts of the Pacific, and elsewhere – there are accounts of indigenous people seeing first European arrivals as ancestors, ghosts or even gods. All over Australia, the term for `white person’ is generally that which designated `ghosts’ or `spirits of the dead’. Some episodes in colonial accounts provide clearer insight into the meaning and specificity of this kind of identification.

In 1838 a woman near present Perth, for example, approached the explorer George Grey, seeing in him her deceased son. Grey tells us that on that understanding she kissed him as tenderly as would any Frenchwoman. The specificity of this identification tells us something about the terms in which indigenous people, where situations unfolded peaceably, were willing to meet outsiders. We also learn about diversity of reception, which warns us against reducing the complexity of interaction to stereotypy. Indigenous people met outsiders with curiosity, with hostility and caution, sometimes with enthusiasm.

Today the reception of outsiders remains diverse, but specific modes of inclusion continue to mark out distinctively indigenous ways of being and acting.

The theme of 'recognition' bookends Dynamics of Difference in Australia. What are some of the ways in which this term has been interpreted differently by indigenous versus non-indigenous Australians over time?

The book develops the theme of `recognition’ historically and into the present, as a question about mutuality, its conditions and content. Captain Cook was the first to note, in Botany Bay, a moment when his ship was well within earshot and sight of indigenous people, that they steadfastly refused to look at or otherwise notice the English arrivals. This was not a one-off. Similar studied inattention in early encounter is reported by close observers across the continent. To not recognize in this way is to refuse engagement. But at the same time, the very refusal tacitly marks acknowledgement of a sphere of mutual attention, even if this is first manifested as apparent inattention.

But to refuse uptake cannot last where the other persists. This episode introduces a theme that resurfaces in many parts of the book, concerning recognition on the one hand, inattention and indifference on the other, across gulfs of difference. The book opens with Cook and ends by considering one of the current manifestations of this issue in the on-going debates about `constitutional’ or other forms of recognition of indigenous Australians and their concerns at the national level.

Will the kinds of differences discussed in the book persist over time?

The part of northern Australia I know best has been undergoing rapid change in how indigenous people have been encountering new influences from the wider society and economy. These include direct and prolonged exposure to a town environment, to more intensive schooling, new forms of resourcing, kinds of housing and structuring of households, land claims, services, shire councils, and related changes in their own social networks and activities.

Under changing conditions there will continue to be new forms of engagement. But I think there will also be continuities in the ways indigenous people live the engagement in their on-going, and generally highly unequal, relations with nonindigenous Australia. As I discuss in the book, some aspects of social action are relatively stable or ‘sedimented’. Some patterns are inculcated and transmitted `under the radar’, in the ordinary ways that people live. These patterns reflect long-term continuities as well as kinds of change, and are shaped by social inequalities.

There is little doubt that the larger society, its institutions and people, had and have the power to affect and disrupt distinctively indigenous ways of being and acting, through both omission and commission. That power to disrupt can only be mitigated by greater autonomy and confidence, and increased ability to come to terms with the larger society, on the part of indigenous people. Change in the terms of difference is inevitable, but complete eradication of difference is not foreseeable.

What do you hope the impact will be of your book, from having people recognise these differences that exist and in gaining a greater awareness of the dynamics between indigenous and non-indigenous Australians?

I hope this book can reach a broad audience, clarify persistent terms of incompatibility in indigenous-nonindigenous relations, and help to address persistent failures of policy to deal with these incompatibilities relationally.