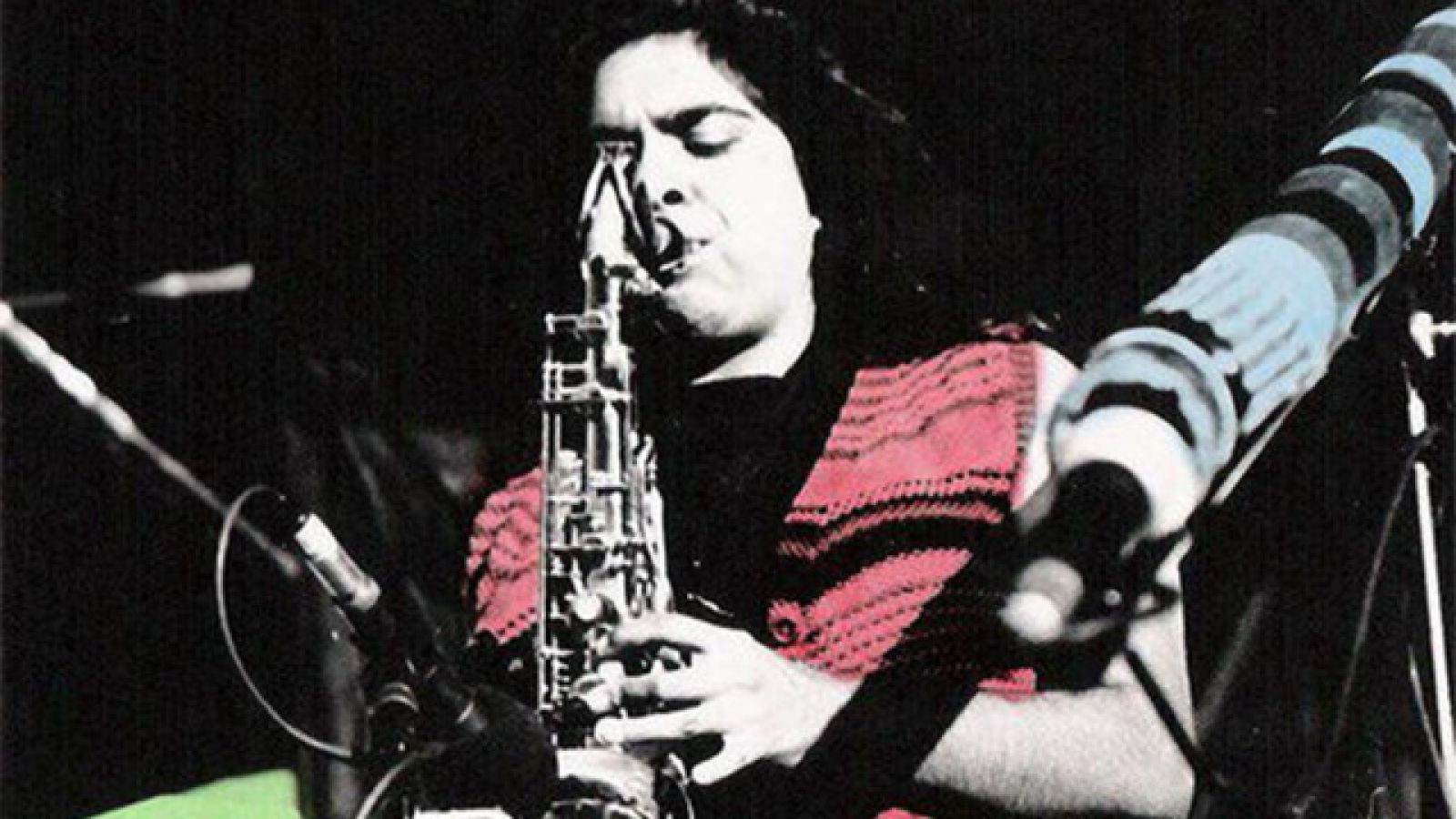

Saxophonist and jazz pianist Brenda Gifford. Photo by Darian Turner.

Composer Dr Chris Sainsbury and saxophonist/jazz pianist Brenda Gifford have been running into each other every ten years.

The first time was in the early 1980s.

“She was playing in a big band in north Sydney,” the ANU School of Music lecturer recalls.

“We were both young, in our early 20s. Anyway, they played some of my music.”

Their second encounter came in the early 1990s, when both were teaching music at Eora College in Redfern.

“We taught together for a while and then her rock band Mixed Relations sort of took off, so she left and went with that.”

Now, in 2017, they’ve been re-acquainted – through the Indigenous Composers Initiative.

Dr Sainsbury established the initiative having learned during his Eora College days that there was a need for a mentoring program to support emerging Indigenous composers. He himself is descended from the Dharug/Eora people of Sydney.

In 2016, Dr Sainsbury’s ambitions were turned into a reality with the help of an Australasian Performing Right Association (APRA) grant. Today, the initiative is well underway with five participants on board – including Brenda Gifford, a Yuin woman from the NSW South Coast.

“It came down to, ‘Can you read music?’” Dr Sainsbury says.

“Have you got an interest or shown a previous background where you’ve done some composing outside of the songwriting circles of rock and roll or country and hip-hop?”

As a classically trained saxophonist and self-taught jazz pianist from Bart Willoughby’s band Mixed Relations, Brenda fit the bill.

She joined the reggae/pop/rock/jazz band in the mid-1980s and stayed, she jokes, for “too long”.

“It was a really great experience,” Brenda says.

“I got to see Australia – urban, regional, remote, traditional. And we got to see a bit of the world – London, Hong Kong, Pacific Islands and America.”

Mixed Relations honoured its Indigenous roots, performing in Indigenous communities, for Koori Radio, and playing in prisons as part of NAIDOC Week. They also achieved mainstream success, reaching #89 on Triple J’s Hottest 100 in 1993 with their single “Aboriginal Woman”.

But for all of Brenda’s experience as a professional musician and music teacher, composing required a whole other set of skills she’d yet to hone. Brenda saw the Indigenous Composers Initiative as an opportunity to develop those skills.

“What you hear in your ear and what is in a written format can be two completely different things,” Brenda explains.

“Chris is kind of guiding me through it – he’s giving me really great examples of techniques. It’s just really nice to be able to sit down and do this with an Aboriginal composer.”

Brenda’s experience aligns with the desire she and the other participants voiced at their first program session. Which was: “We want to drive the cultural content”.

Dr Sainsbury elaborates: “They said, ‘We’re happy to learn new techniques, but ultimately we’re driving the cultural content – what this is going to sound like.’”

“But even deeper than that, the meaning they want to convey within their work.”

What Brenda has been working on through the initiative is a series of pieces akin to an Indigenous version of Vivaldi’s Four Seasons. She’s calling it a South Coast Songline and it’s about the interplay between the seasons and the elements. All the compositions will be in the South Coast Dhurga language.

Brenda has so far been working on this with Kevin Hunt, a composer and jazz musician from the Sydney Conservatorium who is co-facilitating the initiative with Dr Sainsbury.

“He helped me develop a song called Gadhu,” Brenda begins.

“Gadhu is the sea. Then, Galaa – sun, which Chris helped me develop, is a kid’s song that will be performed at this years’ Canberra International Music Festival.

“The current song that I’m working on with Chris is Gambambara – spring. The next song in the series will be Dhagarwa, which is winter.

Dr Sainsbury describes Brenda’s work as being a combination of jazz, classical and ambient music.

“She easily utilises chords that other people might shy away from – really dissonant harmonies,” he says.

“She loves the clashes in music and she uses them artfully, and not just leaving people thinking, ‘What the hell was that all about?’”

Brenda smiles when she talks about the type of music she performs and creates.

“I’m always cheeky in that I say, ‘Aboriginal music is not only clapsticks and didg’.

“We’ve always been there and done it in every genre. We just haven’t necessarily gotten recognition within the mainstream.

“And that’s why it’s really important for programs like this where Aboriginal musicians are given an opportunity and access to develop these ideas.”

In March, the participants will have their first workshop with Ensemble Offspring.

“They’ll work with the performers, the performers might say, ‘You’ve used only two octaves of my instrument, you could’ve used this other octave here as well’,” Dr Sainsbury explains.

“Or, ‘This is clumsy fingering on the cello – why don’t we try it with this other fingering.’

“Our group of five will be getting the same benefits as any composer when they workshop with an ensemble.”

Come July, the wider world will get to hear the works that have been so rigorously developed through the initiative. Ensemble Offspring will debut the works in a performance to be announced.

“The participants are doing really good work in their writing and producing some very mature and strong work,” Dr Sainsbury says.

“It's sort of like it's been there all the time and they've just needed this vessel to step forward and say, ‘Yeah, I'm a composer too.’”