Best, But not fairest? ANU artist continues to champion data sovereignty with Adam Goodes

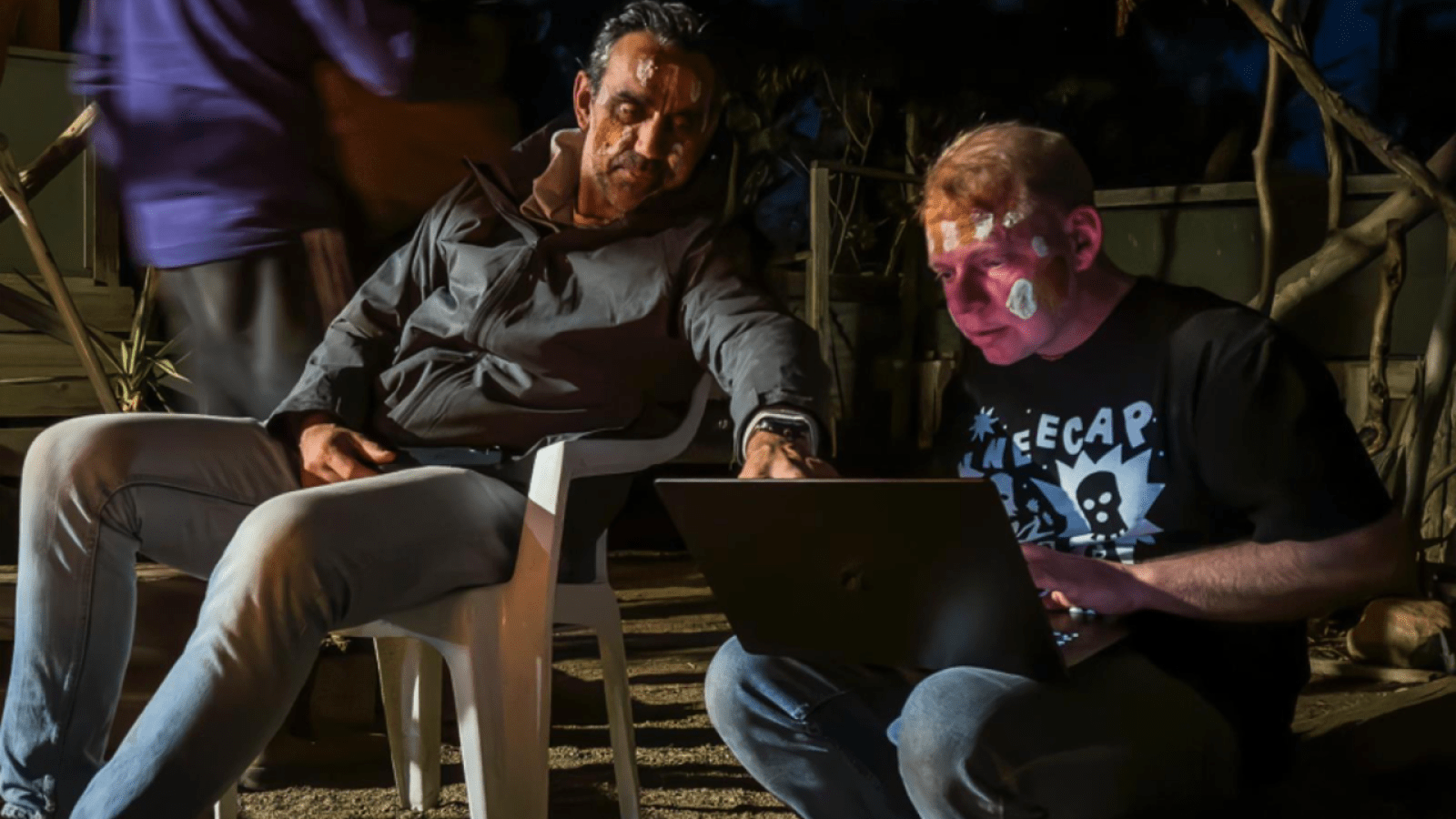

Adam Goodes and Dr Baden Pailthorpe during field work on Adnyamathanha Country, July 2025. Image provided. Credit: Colin Elphick.

Written by Erika McGown.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander readers are advised that the following article contains an image of people who have died.

As any footy fan knows, commentators and coaches love to champion data.

In every AFL match, for example, a GPS tracker logs each player’s co-ordinates, at a rate of 10 times a second. It calculates their speed, acceleration, endurance, and movement patterns. By a game’s end, each one has logged more than 20 million data points.

That’s a lot more data than you’ll ever see in your Spotify Wrapped. And unlike you, who might skip an embarrassing track when you post your playlist, they don’t get to curate it.

Few of us could claim to be as familiar with that truth as Adnyamathanha and Narungga man Adam Goodes.

For most, the 2014 Australian of the Year needs no introduction. But if you were unaware, Goodes is a two-time AFL premiership player and a two-time winner of the league’s fairest and best award: the Brownlow Medal.

Goodes wore data trackers onto the ground in every AFL game he played. For him, their outputs were never just numbers. They were central to his identity.

In his words, “that data captured me playing football, but it also captured me emotionally and how I’m connected to that yarta, that land that I’m playing on.”

He was sharing this with Dr Baden Pailthorpe, a Senior Lecturer at ANU School of Art & Design. He and Goodes first collaborated eight years ago on Clanger, an exhibition to explore the aesthetics of power through data.

Their upcoming exhibition, backed by a $100,000 Creative Australia grant, expands onClanger. Its artworks, like threads in a technological tapestry, spin that data into a yarn of national culture and power. It will be unveiled at the National Portrait Gallery next year.

Performance tool, or surveillance system?

Sports organisations are drowning in data. They collect more than they use, and far more than they need.

A major study from the Australian Academy of Science exposed this, finding that with every sprint, kick, and tackle, players surrender a part of themselves.

This data starts as drone footage, GPS co-ordinates, and medical results. With those building blocks, algorithms construct information.

Even as a player laughs with teammates at quarter time, the trackers fill spreadsheets with numbers. One column logs every last beat of a player’s heart.

Yet, it doesn’t end there. The trackers even follow them off the ground, hovering quietly in the car, the kitchen, the bathroom, and the bedroom. Players’ nutrition, sleep, menstrual cycles, and even gaits are tracked and analysed.

All this surveillance may boost performance, but these gains diminish. When do the risks – privacy breaches, misuse, and psychosocial effects – outweigh those gains?

Even after their bodies sound the siren on sport, all this data remains. Just as our bodies remember rolling an ankle with a click, the spreadsheets hang onto those memories.

Maybe it shows they ran slower that day or made an extra trip to the bench. As data, this information remains tradeable. In professional sport, experiences have become ‘assets’. Goodes and Philthorpe’s work reflects on this.

As Professor Kathryn Henne, Director of ANU RegNet, says, “this project promises important insights into concerns around surveillance practices in sport … [this exhibition] provides [viewers] a more grounded and nuanced understanding of what they are and how to better address them.”

Profiteers are pushing privacy to its limit

The Commonwealth Privacy Act 1988 uses the words “reasonably necessary.”

It notes that organisations have no right to collect information that’s merely “helpful, desirable, or convenient,” or gathered “just in case” it will be necessary later.

Yet, sports data companies push this boundary all the time. They sell all this data back to leagues to hone the “product” – ultimately, a broadcast. This gap between law and reality is a big, immediate risk.

The way governing bodies fail this test is threefold: transparency, necessity, and consent.

These are hard to define, and even harder to protect, especially consent. Lifetime dreams, team solidarity, and contracts are in play. Nobody is truly free from coercion in sport.

When trackers meet hackers

Now, sports data companies claim they can forecast player performance with these numbers using machine learning. This hasn’t yet stood up to scrutiny.

In the NRL, for instance, players reported increased fatigue caused by rule changes introduced for the 2020–21 season.

The league dismissed these concerns, claiming “The Data” proved them false. Until experts can fact-check “The Data,” leagues will invoke it to coerce players, on and off the field.

Even more dangerously, hackers target this data. In 2016, Russian hackers stole data from the World Anti-Doping Agency, and exposed Simone Biles and Serena Williams’ sensitive medical information.

They can use data to spread lies about athletes. As more sports data is stored in cloud-based systems, these risks multiply.

Getting to fair play

Fair play in sport has always meant setting boundaries, whether on equipment, substances, or conditions of competition. Sport data demands the same careful regulation.

Ongoing privacy law reform is working to do that. With clear, enforceable rules, Australia can get sports data collection under control. That means meeting public expectations.

Stronger athlete data rights would also align Australian law with international standards, such as the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation.

Players’ unions in the AFL and rugby codes have won some data rights in enterprise bargaining negotiations. This is a start, but it isn’t the systemic protection they need.

Where culture comes in

Data ownership is bigger than privacy law and data profiteering. Sport is cultural, and so are its stories, even in the form of data. Especially for many Indigenous athletes.

So, Dr Pailthorpe and Goodes’ project is a powerful cultural gesture. Their primary subject matter is Goodes’ ancient craft: Australian rules football.

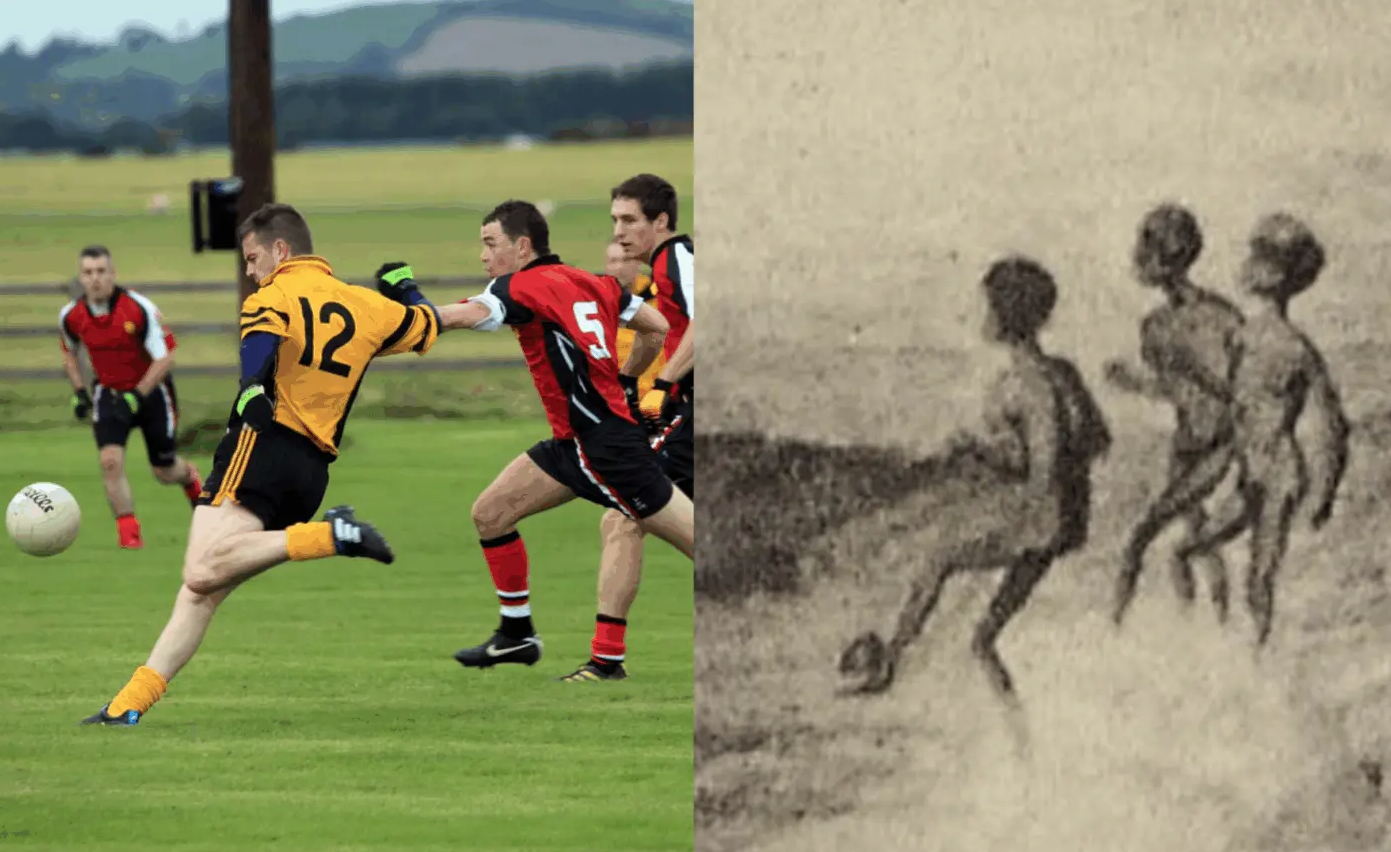

I say ancient, because Australian football is likely an iteration on Marngrook, a sport made by Aboriginal Australians before European settlement.

In 2019, the AFL apologised to Goodes for failing to address racism directed at him as a player.

In the same statement, it recognised this history, declaring that Marngrook “undoubtedly influenced what we now understand as the modern AFL football code.”

Australian rules also resembles Irish indigenous sports: Gaelic football and hurling. So, today’s rules may have been agreed between Celtic settlers and Aboriginal Australians.

If so, they emerged from the colonial encounter itself.

Dr Pailthorpe says the exhibition is part of the Indigenous Data Sovereignty (IDS) movement, which “is about Indigenous people taking control of data that is about them, and that affects them.”

According to Professor Maggie Walter, the IDS movement pushes governments to recognise First Peoples’ right to govern the collection, ownership, and application of their data.

These numbers hold stories of Country: people, their movement, their life on the land, and what they and the land do for each other.

In professional sport, Indigenous athletes are disproportionately well-represented. So, questions of sports data sovereignty are urgent for the movement.

As Goodes and Pailthorpe’s work reminds us, data is power. Yes, power to harm, but also power to help athletes thrive – if we listen to their voices as we collect, share, and use data.

As Goodes’ Ngami (kinship mother), Aunty Glenise Coulthard AM says, “This project is about bringing Adam’s football data back to Country … [it] adds to the fabric of Adnyamathanha Culture, and Yarta.”

This article was originally published by ANU Reporter, here.